ABSTRACT

During the American war in Vietnam, the U.S. military sprayed over 600,000 gallons of dioxin-contaminated Agent Orange and other toxic herbicides over vast parts of the Ho Chi Minh Trail established on southern Lao territory. Most of the area the Trail consisted of—in Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia—was remote and covered by the thick jungle canopy of Southeast Asia. To date, very little is known about the full extent of the human health consequences of the wartime herbicidal spraying in Laos. But the observed occurrences of similar types of birth defects among those living in villages near or abutting wartime spray routes have, in recent years, raised concerns about the impact of the herbicides in Laos. During a period of three years, War Legacies Project surveyed 126 villages in five of the districts of Salavan and Savannakhet provinces heavily sprayed with herbicides. Among surveyed villages, with an average population of 250, there was an average of four people with visible birth defects. Two-thirds were under the age of 20, and more than half were under the age of 16. For those most at risk there was and remains a dire need for medical care and rehabilitation services. WLP continues to encourage and advocate for greater U.S. support and for the wider recognition of especially immiserated people in Laos suffering from maladies and conditions associated with Agent Orange exposure.

In the Lao People’s Democratic Republic a key challenge to poverty alleviation and development is addressing the legacies of the U.S. Secret War in Laos (1961-1975).

While much of the attention of the international community has focused on unexploded ordnance (UXO), little is known about the impacts of the war’s herbicide spraying. As in Vietnam, Laos’ southeastern border region was subjected to nine years of heavy carpet-bombing and repeated herbicide spraying. But unlike Vietnam, the generational impacts of wartime herbicides on the Lao population and environment have been neither fully surveyed nor accounted for nor mitigated. Little was known about herbicides being used in Laos at the time and this has had devastating consequences in addressing its ongoing legacies today.

The hidden health and environmental dangers of herbicide spraying have compounded many livelihood problems for those living in this southeastern region comprising 15 border districts. Various socio-economic indices reveal the uneven and slow development of a profoundly impoverished region lagging behind the rest of the country.[1]

Until recently, most of the region’s remote villages were inaccessible by road. Some still are only reachable on foot. The lack of a viable transportation infrastructure placed people with physical challenges and disabilities at an even greater disadvantage. As a result, many have been unable to access medical care, rehabilitation services and educational opportunities, all of which lead to increases in poverty.

1. HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY OF TOXIC SPRAYING

During the wars in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, the Vietnamese and their Lao and Khmer allies built a network of paths that came to be known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail (Đường Trường Sơn).

It was a military transport route that twisted through the mountainous spine of the Trường Sơn/Phou Luang Range, under the cover of dense jungle canopy. The Trail extended into the territories of officially neutral Laos and Cambodia bordering southwest Vietnam. Covert U.S. combat warfare and bombing operations began focusing intensively on bombing and herbicide spraying of the trail in southeastern Laos in 1965.[2]

Laos and Vietnam, as well as parts of Cambodia, became primary targets of the U.S. counterinsurgency program code-named “Operation Ranch Hand.” Operation Ranch Hand was the U.S. Air Force defoliation, crop destruction and food deprivation program that deployed nascent airwar techniques in its application of nearly 76 million liters of toxic “rainbow”[i] herbicides on Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.[3]

The objective was to denude the tropical-agricultural landscape that had provided both subsistence and cover for on-ground insurgents.

According to official records over 2,271,247 liters of herbicides were sprayed by planes over 66,773 hectares along the Lao side of the Ho Chi Minh Trail between December 1965 and October 1970.[4] These records, however, are incomplete, as declassified CIA Documents reference defoliated areas of the trail as early as November 1964.[5]

The sprayings in central and northern Laos, though sparse and isolated, have been confirmed by public official records.[6] The majority of the spraying, however, occurred along and near the southeastern Lao border with Vietnam. Five Lao provinces that were impacted include:

- Khammoune Province.

- Savannakhet Province.

- Salavan Province.

- Xekong Province.

- Attepeu Province.

Some of the most intense sprayings in Laos occurred in 1966 when nearly 1.5 million liters of the herbicides rained down over 3200 kilometers of the tangled paths that comprised the Ho Chi Minh Trail. [7] During the war, over 500 villages were located within 10 kilometers of the spray paths.

Many villages in the districts of Xepone, Nong, Ta-Oey, Samoi, Dak Cheung, La Mam, Kaleum and Phouvong were sprayed multiple times.

In recent years, efforts have been made to redress the severe economic disparities between this heavily sprayed southern region and the rest of Laos. But today, this particular southern region still remains comparatively underdeveloped. There are an estimated 500,000 people living in 800 villages. In the 2015 census, about 75 percent of these residents lived in rural areas, 15 percent had no road and only rough access tracks during the rainy season, and over 50 percent, excluding those residing in Attapeu province, suffered extreme poverty. [8]They are primarily subsistence upland rice farmers with limited access to the cash economy.

Agent Orange and Human Health Impacts

Agent Orange, specifically the 2,4,5-T component, was contaminated with 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), also known as Dioxin. Dioxin belongs to a family of more than 70 isomers of highly toxic, man-made organic compounds created during industrial processes and waste incineration. The term “Dioxin” is commonly used to refer to the TCDD specifically found in Agent Orange—and also in Agents Pink, Purple, and Green—the most toxic of all Dioxin-like substances.

Dioxin is now recognized as a known human carcinogen and has been shown to be teratogenic (birth defect-inducing) in all species of animals that have been studied.[9]

Dioxin Hotspots

Unlike in Vietnam, there are no known major Dioxin hotspots—that is, Dioxin-contaminated areas—in Laos.

The bases of operations for most of the aerial spraying missions in Laos were in Vietnam and Thailand. There were over 400 former landing strips, airports or spotter bases of operation in Laos that were part of the U.S. war effort.[10] [11] As in Vietnam, it is possible that herbicide barrels may have been stored at some of these bases for perimeter spraying or to be loaded onto planes. As a result, some may be potential Dioxin hotspots.

Research by WLP and Hatfield consultants in 2014 estimated that approximately 30 of these former U.S. paramilitary sites may warrant further investigation for potential Dioxin contamination due to the fact that they were under U.S. or U.S. allies’ control for at least 3 years and are located in populated areas.[12] If such hotspots exist, however, their levels of Dioxin contamination would be comparable to the levels found at the former special A So base in A Luoi District, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam. The A So base was used for a period of several years by the U.S., and the Dioxin level in the soil found in 1999 by Canadian-based Hatfield Consultants was just under 900 ppt. This level of contamination required the relocation of the nearby village and the installation of a fence to keep people and livestock out.

Unlike in Vietnam, very little testing of soils for Dioxin has been conducted in Laos. But in 2005, in Dak Cheung District, Xekong Province, Canada-based Hatfield Consultants found elevated levels of Dioxin at the landing strip of the former Chavan airbase. Although lower than required for remediation at 37.8 ppt and 31.5 ppt, this was much greater than the background level of between 1 - 11 ppt in rural soils and was nearly 90 percent TCDD indicating Agent Orange was the likely source of the contamination. During the short period the strip was under U.S. military control local residents reported to Hatfield researchers that they recall seeing orange-striped barrels being buried in the area.[13]

Because the full extent of the war effort in Laos is still unknown, it is likely that many U.S.-controlled bases established throughout Laos have equally elevated levels of contamination.

We know that for a short period in 1968, Air America pilots used the Porter (XWPCB) plane outfitted with spray nozzles to spray Agent Orange on SkyLine Ridge above the CIA base Long Tieng (LS-20A) and in Na Khang southeast of LS-36 in northern central Laos.[14] It is unclear where these barrels of herbicide were stored and also where and how herbicides were loaded onto planes. Soil sampling at Long Tieng may be required in the future as it is now being developed into a district capital town.

It is also possible that heavily and repeatedly sprayed villages in southeastern Laos are potential Dioxin hotspots and bear further investigation. Lahang village near the Vietnam Border in Samoi District, Salavan Province, for instance, has high rates of congenital birth defects and sits at the base of a hillside that was heavily sprayed. Years of heavy rainfall may have resulted in pools of Dioxin in the village. There are approximately 12 other possible hot-spot villages in Samoi along the route from the Vietnam Border towards Ta-Oey District in Salavan and Nong District in Savannakhet.

Environmental testing could confirm whether pockets of Dioxin contamination remain in Laos. It should be conducted both 1) in areas where there is a high likelihood of human exposure such as the more heavily used landing strips and bases in Laos and 2) in villages where there are high rates of persons with congenital malformation. We estimate that the question of Dioxin hotspots in Laos could be put to rest in a matter of several years with a small but robust environmental testing program.

2. THE LAOS AGENT ORANGE SURVEY

Since 2015, War Legacies Project has been conducting a systematic recording and collection of statistical data on the potential impacts of Agent Orange in 126 villages in 5 of the 15 districts impacted in southeastern Laos.

These initial efforts have been part of the Laos Agent Orange Survey, which was launched to determine the extent of herbicide contamination and its human health consequences—to find the prevalence of congenital malformations and/or disabilities in previously sprayed regions. During this first phase of the survey WLP focused on selected villages in the five heavily sprayed districts of Samoi and Ta-Oey in Salavan Province and Nong, Xepone and Vilabouly districts in Savannakhet Province.

A majority of the villages had at the very least one person with a congenital malformation. The average was four cases per village. The most common birth defect found was hip dysplasia, followed by paralysis and then cleft-lip and/or cleft palate.

Figure 1. Types of Birth Defects Found

The Laos Agent Orange Survey focused on identifying people with external birth defects and/or congenital disabilities born after 1966. Their conditions, in order to be included in the Survey, must be categorized according to what is recognized by the VA and/or the Vietnamese government.[15] [16]

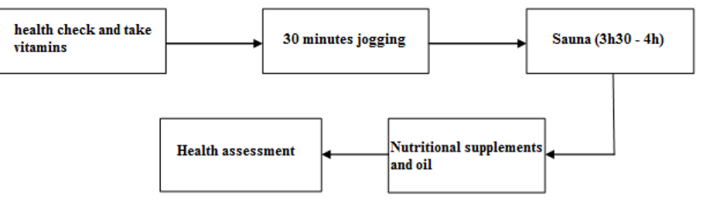

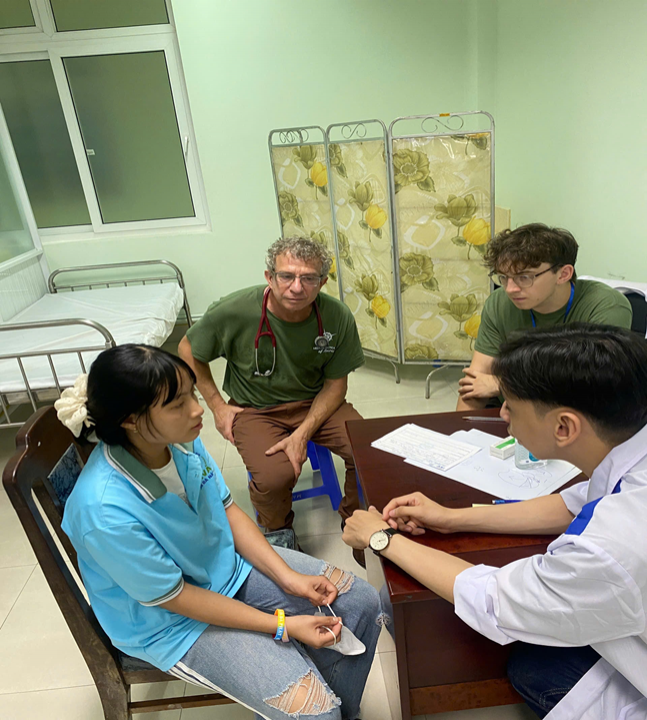

WLP conducted the survey whenever possible with the assistance of local medical staff from district hospitals. Importantly, few local medical staff are trained to identify congenital birth defects and are usually newly graduated in-training medical students.

More than half of those identified in the survey, or 270 children, are below the age of 16, and two-thirds are under the age of 20. This means they would be the third and possibly even some the fourth generation since spraying took place. In addition, 57 percent are male, and 43 percent female. Since 2017, 9 of these children have died from complications of their birth defects and 2 young adults from cancer.

Figure 2. Birth Defect by Generation.

* There appears to be a correlation between the number of spray runs near a village and the number of people born with birth defects.

Because the survey was able to reach all 51 villages of Samoi District, Salavan, and all are within 6 miles of the spray runs, it is possible to compare the villages that are near the heaviest spraying with those further away. Fourteen of the villages near where multiple spray runs were conducted tended to have more people than average (more than 4 per village) born with congenital disabilities. This includes the village of Lahang with an estimated population of 528 in 2018. It is near the border of Vietnam and the survey found 17 persons with congenital disabilities.

Kou Tai, with an estimated population of 313, less than 2 km from the Vietnam border, had 8 persons with birth defects and 2 with epilepsy; Kava-Tava, with a population of 274, and 6 kms from the border, had 12 persons with birth defects; and Acheungngai, with a population of 327, and 9 km from the border, had 9 persons with birth defects and 2 with epilepsy.

This disproportionate prevalence is even more apparent when you add suspected cases of congenital epilepsy into the calculation as it adds six more villages with greater than average persons with congenital disabilities.

3. SUPPORT PROVIDED BY WAR LEGACIES PROJECT

Of the 517 people identified in the survey, about 25 percent have been sent or accompanied by WLP to provincial and national level hospitals for further examinations and/or treatment.

Priority was given to those for whom life-saving or life-changing surgeries or medical intervention could be performed within Laos. Hence children with cleft lip and/or cleft palate, club foot, severe scoliosis and arthrogryposis were prioritized. Others with more complicated cases were referred to specialists from outside of Laos who were visiting on medical missions.

In order to facilitate direct support for persons with disabilities, WLP identified and worked with local partners—the District Department of Labor and Social Welfare, the District Women’s Union, district hospitals and Nai Bans (village heads). These partnerships, however, have been limited to cases of medical interventions that could be performed by visiting medical teams, or in a few exceptions across the border at the Hue School of Medicine Hospital.

There are other challenges. For example, several young adults and children with cases of hip dysplasia traveled to the provincial rehabilitation center to receive orthotic lifts to level out the length of the legs, control abnormal motion and provide heel correction. Later it was discovered that many of the orthotics had not been used adequately, if at all.

Nonetheless, providing services in conjunction with the surveying work has helped WLP staff to build trust among many of our beneficiaries and their families, especially children.

Priority was also given to children in order to ensure early intervention through various WLP programs. Children receive the most assistance in the form of rehabilitation services and medical interventions in order to mitigate complications and ensure integration into their peer group as the child matures.

Some of the children who were previously unable to walk due to severe clubfoot are now able to run and play with their peers and attend school. Children who had cleft lips or palates no longer faced the stigma attached to their conditions after WLP-provided services.

Persons with disabilities unable to walk on their own now have wheelchairs and/or home renovations to build accessible home amenities. The costs to bring a child from remote areas to Vientiane and to other larger cities to access health facilities for care or surgeries can total up to $400 or more. The biggest expense is the travel costs for the child and one or two caregivers and living expenses while away from home. WLP usually provides financial assistance to help offset logistical costs such as transportation that are out of reach for most families.

WLP has also supported persons with disabilities by sending them to Vientiane to receive training. Most have been teens and young women. Seventeen youths enrolled in vocational training programs while women received training in sewing, weaving and other handicrafts at the Women’s Disabled Development Center or at the SiKeurt Vocational center.

4. EXISTING SUPPORT FOR PWD IN THIS REGION AND IN LAO PDR

* Lao Government:

With limited resources, the Lao authorities have made great strides in improving and providing access to medical care, vocational training, inclusive education and social integration for people with disabilities. In 2014 they passed the Decree on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Medical care is free or deeply subsidized by the Lao government for people with disabilities and the poor up to the provincial level of care. But in the southeastern region of Laos the quality of health care at the district hospitals is rudimentary. For more specialized care one needs to travel to the provincial capital or national capital in Vientiane.

* Children’s Food Programs:

Most of the schools in Laos including those in the southeastern border region have a school-based program to provide meals to students to combat child malnutrition and stunting. But unless the child with a disability attends school, they do not benefit from this program.

* Provincial and National Hospitals:

Some procedures to address congenital malformations such as cleft-lip and club foot can be addressed at the provincial hospitals in Savannakhet and Salavan. But more advanced procedures such as to address cleft-palate, spinal malformations, complex facial surgery, stents for hydrocephalus, and most orthopedic conditions must be conducted at one of the national hospitals in Vientiane. Visiting teams of specialists also travel to Laos to train Lao doctors in early detection of birth defects and intervention treatments. These medical missions, for the most, do not ever reach the southeastern districts.

* UXO Victims Program:

The UXO Victims Program is focused on providing orthotic and prosthetic devices and rehabilitation for people who have been injured when unexploded ordnance (UXO) is set off. Their care is provided free of charge by the UXO victim’s support program, funded in part by the U.S. government. But children with congenital malformations who could use the same types of assistance often must pay for these services. Fortunately, the training that is provided to support people impacted by UXOs is also benefiting those who have missing limbs due to birth abnormalities.

* Okard:

The U.S. is currently funding the five-year Okard project in Vientiane, Xieng Khoang, and Savannakhet that provides training in health and rehabilitation services for persons with disabilities, supports vocational training programs and livelihood opportunities and helps coordinate government and non-government organizations that support persons with disabilities to advance their rights. But it does not reach the rural populations in the border regions that were heavily sprayed with herbicides. Nonetheless, the training that is provided for rehabilitation specialists and medical professionals in Savannakhet and Vientiane will benefit those PWDs from the rural regions who need to travel for more specialized care.[17]

* Center for National Rehabilitation:

The CNR does have satellite branches in Pakse and Savannakhet provincial capitals. They are best trained to address missing limbs from unexploded ordnance. They are ill-prepared to handle conditions of physical disabilities where paralysis and/or muscle wasting is present. Moreover, they are ill-prepared to address cognitive impairments. For most rehabilitation programs it is necessary to travel to Vientiane to the CNR which often requires a long stay.

* Inclusive Education Programs:

Catholic Relief has worked to ensure that children with disabilities are integrated into the education system and the community including in Nong, Xepone and Villabouly districts. ChildFund Laos, Plan International, World Vision and Save the Children have in the past conducted inclusive education and medical screening in Xaybouathong, Khammouane Province through the BEQUAL Program funded by AusAID, the European Union and the Lao Government.[18]

But these programs have not reached most of the border districts in southeastern Laos which were heavily sprayed by herbicides. Still, the lessons learned from these programs can be useful in developing programs in the more remote districts of southeastern Laos.

Programs could provide PWDs and their caregivers regular medical check ups, non-formal education classes, vocational training and teams of social assistants trained in basic care of PWDs who speak the local languages and can assist families when traveling to large medical facilities.

5. CHALLENGES IN PROVIDING MEDICAL CARE

- Most persons with disabilities have never visited a doctor so very little trust in the medical profession has been established. Villagers more often rely on traditional medicine and healers.

- There is little awareness that medical intervention at the early stages may be possible for addressing some of the birth defects or illnesses such as arthrogryposis, club foot and hip dysplasia.

- Health professionals in district hospitals have limited training in how to identify unusual disabilities and medical conditions. In addition, they have not been trained on how to work with people with disabilities and their families to address their unique concerns.

- Most medical professionals at the district and provincial levels are unable to communicate in the local ethnic languages hindering communication with PWDs and their care-givers. Many living in border areas are ethnic minorities who have very rudimentary Lao language skills and very low literacy levels and therefore need constant guidance.

- There is no formal system of trained medical social workers in these areas to assist children and adults who have physical and/or cognitive challenges in navigating the complex medical and rehabilitation system in Laos.

- The local village medical clinics are not equipped or trained to handle patients with complex birth defects or disabilities. They must refer the patients to the District level medical facility who in turn will refer them to the proper level of care at the provincial or national level. Local village medical staff may not be aware of specialized assistance available at higher levels of health care. As a result, families often return home if medical care is not available at the local level instead of traveling to the district, provincial or national level facility.

- Most affected persons are poor upland rice farmers who do not have access to the cash economy to support even bus travel to provincial or national level medical facilities. Travel to a major hospital even at the province level is often financially prohibitive.

- Traveling to the district capital for medical care or to reach transportation to the provincial capital is daunting. Many villages are accessible only by foot, motorbike or four-wheel drive vehicles and only during the dry season. Even then it can take several hours as modes of transportation are very limited. Many of the villages are still inaccessible in the rainy season.

- Travel for medical care must be scheduled around the family’s agricultural work schedule and the dry season.

- Children who require surgery often need to stay weeks or months in hospitals far from home. Most hospitals have no facilities yet for specialized playrooms, books and other learning tools for children and young adults. Thus, patients become bored very quickly and are anxious to go home before treatment is even started or finished. Accompanying caregivers need financial support to cover living expenses while away from home.

- A young child with a disability often needs to have two caregivers travel with them. Consequently, scheduling child care at the home village can be difficult for families with young children.

- Medical expenses are covered by national insurance only if the person follows the referral procedure and only for medical care up to the provincial level. If the child needs to travel for care at a Vientiane facility the cost is not covered by government insurance.

- Many young children with disabilities have other underlying medical issues and malnutrition. Children with severe disabilities that are unable to go to school are then deprived of the school feeding programs established to combat malnutrition in this region.

- Communications with families to coordinate travel for medical care is difficult as most can not afford a cell phone. Communications with the families often must be coordinated through the district level government staff and the Nai Ban (village head).

- When patients and caregivers are able to travel for medical services they find themselves confused navigating the medical system and adjusting to the urban environment. A system of young volunteers as guides would be helpful to give patients and caregivers assurance and proper information.

- If complex surgery is required, caregivers will often want to travel back to their village to confer with elders as well as perform rituals to be certain their village spirits support proceeding with surgery.

- Lao doctors and surgeons even at the national level do not yet have sufficient training to address complex birth defects. Many conditions require the care of a visiting team of specialists and their surgery schedule books up very quickly. Some children, such as those with arthrogryposis, often require multiple years of surgeries in the most complex cases

- Children with paralysis, cerebral palsy and other movement disorders have no access to rehabilitation services at the district level. Even if they are able to travel to the provincial capital for extended rehabilitation there are very few trained rehabilitation staff and even fewer that have specialized training to address their needs.

6. RECOMMENDATIONS

The above and other programs for persons with disabilities in Laos provide a good foundation to build upon for future programs targeted at those with congenital malformations and disabilities in the heavily sprayed regions of Laos. Listed here is some of the work that remains to be done:

- Focus more of existing U.S. government and other international assistance on the Lao PDR in the districts where Dioxin-contaminated herbicides were used by the U.S. government during the war. This should start with the 15 most severely impacted districts along the former Ho Chi Minh Trail of southeastern Laos.

- Release the locations of all covert sites where the CIA and covert military operations may have conducted herbicide spraying by hand and by helicopter or covert aerial spraying. This is necessary to prioritize where environmental testing needs to be conducted.

- Conduct limited testing of soils and sediments, fish and animals, and human breast milk in select villages with high rates of people with disabilities. Conduct similar testing in areas where there is a possibility of the storage of herbicides or frequent perimeter spraying during the war.

- Train medical professionals at the district, provincial and national levels in early detection and early intervention for birth defects.

- Continue to train medical specialists in orthopedic surgery, neurology, plastic surgery, cardiology, spinal surgery and pediatric surgery.

- Grant persons with disabilities travel and food stipends to enable them to travel with a caregiver to hospitals at the national or provincial levels for specialized services.

- Assist the Lao government in establishing a medical social work system. This would greatly help families of children and adults with disabilities to navigate through the complex medical referral system in Laos and communicate with medical professionals.

- Support the provincial and district hospitals to develop village-based medical screening programs with specialists from the national and provincial hospitals that can travel with a four-wheel drive to remote villages to conduct medical examinations and refer people for services.

- Establish non-formal education programs for children and young adults with disabilities and special learning needs who were or are unable to attend school in their villages.

- Establish rehabilitation centers and vocational training programs at the district level to assist persons with disabilities from the heavily sprayed districts. Improvement of the road network would allow a single center to service several districts.

- Foster more communication between the programs for people with disabilities to make it clear which costs are covered by medical insurance and which costs are covered by international programs supporting people with disabilities.

- Develop livelihood support programs to enable youths and young adults with disabilities to have an alternative to upland rice farming in rural villages of southeastern Laos.

- To combat child nutritional deficits, expand the school feeding program to include homebound children with disabilities.

7. CONCLUSION

The amount of funding needed to address the potential ongoing impacts of Agent Orange in Laos would be a small fraction of the $230 million that has been allocated by the U.S. since 1993 to address explosives in Laos.[19] It would be a fraction of the $390 million already allocated to Vietnam for the health and environmental impacts of Agent Orange there.[20] While environmental testing may possibly reveal minimal Dioxin hotspots in Laos, none will compare to the hotspots at the Da Nang and Bien Hoa Airbases. Mitigation measures would most likely require at most the relocation of populations who are living or farming on contaminated soils until the soil can be remediated as was done at the former A So special forces base in A Luoi, Vietnam.

While there are hundreds of thousands and potentially millions of people with disabilities and health issues associated with exposure to Dioxin-contaminated herbicides across at least 10 provinces in Vietnam, those most impacted in Laos are restricted to the 15 districts in the 5 Lao provinces along the border with Vietnam.

Medical screening and educational assessments would need to be completed in the 800 villages that were heavily sprayed. A mobile screening program should be developed to help identify other health and educational needs facing these small ethnic communities.

Lessons learned from OKARD, BEQUAL and programs in other regions of Laos will help in the development of necessary programs with district-level government agencies and ensure capacity building of local Lao agencies and organizations. The aim will be to address the particular educational and medical needs of those in the underserved southeastern region of the country.

With an average of four people with congenital birth defects and/or disabilities per village in the heavily sprayed regions in Laos, WLP estimates that between 3,200 and 5,000 will require specialized programming. This is a very manageable number. In a matter of a few years the U.S. government could fund programs that will alleviate this forgotten and long neglected legacy of the war in Laos.

Susan Hammond

Executive Director, War Legacies Project

REFERENCES

- BEQUAL (2019), \"BEQUAL News and Events Publications.\" BEQUAL. January. Accessed 11 29, 2021. http://www.bequal-laos.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/BEQUAL-NGO-Consortium-Final-Evaluation-Report_Jan2019_for-publication.pdf.

- Birnbaum, Linda (2004), Dioxin, What Citizens, Workers and Policy Makers should know (April 19). https://agentorangerecord.com/interview-with-dr-linda-birnbaum-about-dioxin/.

- Buckingham, William A. (1982), OPERATION RANCH HAND. The Air Force and Herbicides in Southeast Asia. 1961-1971. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History United States Airforce.

- Bureau, Lao Statistics (2015), Results of the Population Census 2015. 2015: Lao Statistics Bureau.

- CIA (1964), \"MILITARY AREA BAN NA HI, LAOS 16-45N 106-08E.\" Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room. CIA. November 23. Accessed 11 29, 2021. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP80T01471R000100010003-8.pdf.

- Flight Information Center Vientiane (1970), \"The Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Vietnam Archives.\" Texas Tech University. April 30. Accessed 11 29, 2021. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/images.php?img =/images/1925/ 19250103005B.pdf.

- Flight Information Center Vientiane (1970), \"The Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Vietnam Archives.\" Air Facilities Data Laos Part A. April 30. Accessed 11 27, 2021. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/ images.php?img=/ images/ 1925/19250103005A.pdf.

- Hatfield Consultants and Environment Research Institute Water Resources and Environment Administration (2009), \"Assessment and Mitigation of an Agent Orange Dioxin and Landmine/UXO Hotspot in Sekong Province, Lao PDR.\" Vientiane, Lao PDR.

- Hatfield Consultants (2005), \"Enabling Activities to Facilitate Early Action on the Implementation of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Polutants (POPs) in the Lao PDR.\" Vancouver, Canada.

- Hatfield Consultants (2014), \"Site Prioritization for Risk Assessment: Screening Former Military Sites in Lao PDR From the Second Indochina War for Potential Human Health Risks.\" Vientiane, Lao PDR.

- Kinne, Col Harold (1969), \"Memorandum for Record: Out of Country Defoliation.\" Saigon: Headquarters US Military Assistance Command Vietnam, January 18.

- Martin, Michael F. (2021), \"Congressional Research Service.\" Congressional Research Service. January 15.

- Ministry of Planning and Investment, Lao Statistic Bureau (2016), \"Where are the Poor.\" Vientiane, Lao PDR.

- Prados, John (1999), The Blood Road: The Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Vietnam War. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Socialiset Republic of Vietnam (2006), Socialist Republic of Vietnam Government Portal. 6 30. Accessed 11 29, 2021. http://datafile.chinhphu.vn/ file-remote-v2/ DownloadServlet? file Path=vbpq/ 2016/09/20-BLDTBXH. signed.pdf.

- Stellman, Jeanne Magar and Steven D. (2021), Agent Orange Data Warehouse. 11 29. http://www.workerveteranhealth.org/ milherbs/new /index.php.

- US Department of State (2021), \"To Walk the Earth in Safety 2021.\" US Department of State. Accessed 11 29, 2021. https://www.state.gov/ reports/ to-walk-the-earth-in-safety-2021/.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. n.d. Birth Defects in Children of Vietnam Veterans. Accessed November 29, 2021. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/ exposures/agentorange/birth-defects/ children - women -vietnam-vets.asp.

- USAID (2020), \"USAID News and Information USAID Okard.\" USAID. February 19. Accessed 11 29, 2021. https://www.usaid.gov/ laos/fact-sheets/usaid-okard.

[1] (Ministry of Planning and Investment, Lao Statistic Bureau 2016)

[2] (Prados 1999)

[3] (Buckingham 1982)

[4] (Hatfield Consultants 2005)

[5] (CIA 1964)

[6] (Kinne 1969)

[7] (Hatfield Consultants 2005)

[8] (Bureau 2015)

[9] (Birnbaum 2004)

[10] (Flight Information Center Vientiane 1970)

[11] (Flight Information Center Vientiane 1970)

[12] (Hatfield Consultants 2014)

[13] (Hatfield Consultants and Environment Research Institute Water Resources and Environment Administration 2009)

[14] (Williams 1990)

[15] (US Department of Veterans Affairs n.d.)

[16] (20/2016/TTLT-BYT-BLĐTBXH 2006)

[17] (USAID 2020)

[18] (BEQUAL 2019)

[19] (US Department of State 2021)

[20] (Martin 2021)

Comment